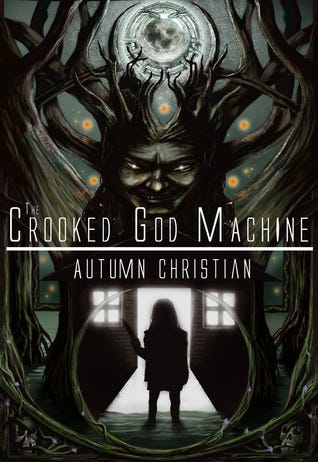

Autumn Christian's The Crooked God Machine and the Theology of Suffering

A Metaphysical Descent into Mechanized Horror and Existential Collapse

There is a peculiar weight to The Crooked God Machine, a pressure that does not relent, immersing the reader within a totalizing mechanism of existential decay. The novel does more than depict horror; it constructs a world where pain is procedural, where every act of despair is an inevitability. Autumn Christian has crafted a reality in which suffering is foundational. Choices dissolve into the slow realization that escape was never part of the design. In this, Christian’s novel resonates with the literary abyss of Crime and Punishment, where suffering functions as both an instrument of control and a philosophical confrontation. Dostoyevsky offers the possibility—however distant—of redemption, while Christian presents a system in which transcendence remains an illusion.

The setting moves beyond conventional dystopia, transcending mere exaggeration of political mechanisms or social critique. It is a theological autopsy, a world in which divinity manifests as mechanized control, where faith and authoritarianism merge into a single apparatus. The novel’s oppressive atmosphere is omnipresent, infused into governance and the very physics of its reality. Christian’s Edgewater, much like Dostoyevsky’s St. Petersburg, is designed to consume its inhabitants, eroding individual agency beneath the weight of an unseen but omnipotent order.

Charles, the novel’s protagonist, exists as a condemned subject, shaped by a system that robs him of autonomy. Like Raskolnikov, he exists in a state of interior collapse, a consciousness constantly at war with itself. While Dostoyevsky’s protagonist agonizes over guilt and consequence, Charles endures a torment that exists beyond morality. His suffering is systemic, preordained, written into the machinery of existence long before he was born. If Crime and Punishment explores the psychology of transgression, The Crooked God Machine dismantles the very idea that transgression was ever possible.

The novel constructs a world where the structure of reality ensures perpetual suffering, where God—if such an entity can be named—manifests as a malignant force. Dostoyevsky embeds suffering with the potential for purification, whereas Christian depicts suffering as a recursive force, a cycle that neither teaches nor transforms. This is not existentialism in the Sartrean sense, where meaning is constructed through rebellion, but a form of theological nihilism where rebellion itself becomes an empty gesture.

The narrative aligns itself with this principle of inevitability. Charles does not progress toward resolution or descend into madness in a conventional sense. His fate is already determined, and the novel merely reveals the scope of his entrapment. This is where Christian’s work most forcefully aligns with Dostoyevsky’s: in the weight of an environment that shapes both character and reader alike. St. Petersburg suffocates Raskolnikov with its claustrophobic streets and sickly air, while the industrial decay of The Crooked God Machine grinds Charles into something unrecognizable. These spaces do not simply house suffering; they refine and perfect it.

The possibility of escape remains an illusion. The machine turns, indifferent to resistance or submission. In Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov dreams of a world overcome by plague, where men tear each other apart in a frenzy of violence, convinced of their own righteousness. In Christian’s novel, this fever is no dream—it is the natural state of things. No past order waits to be restored, no future reprieve can be hoped for. The cycle continues, the ritual of pain repeats indefinitely.

Dostoyevsky allows for salvation, even if only at great cost. Christian does not introduce the prospect. The machine grinds forward, its gears consuming those trapped within. This is the final horror of The Crooked God Machine: suffering is not a deviation but the structure itself. The book does more than tell a story; it forces the reader into confrontation with an impossible question. If suffering is not a means to an end but the end itself, what then?

It is a question that lingers long after the final page, a demand for reckoning rather than resolution. The Crooked God Machine does not present horror as an aesthetic or allegory. It presents horror as a metaphysical condition. It is the terror of realizing that the world is exactly as it appears to be, with no act of faith or defiance capable of altering its course.